7. Process Manager #

What is a Process? #

A process is the unit of work in a computer system.

A sequence of states (for example steps in fetch-execute cycles), resulting from the action of a set of instructions on the states as they develop.

How does the Operating System Manage Processes? #

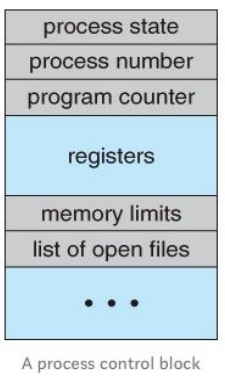

The operating systems maintains a data structure known as a Process Control Block for each process. It contains the current process state, the next instruction to perform, and the currently allocated devices to the process.

This enables the operating system to manage different processes effectively, by saving the current state in the Process Control Block, switching between them and reloading certain processes later on.

Aspects of a Process #

- Static Part: Task - resources allocated to the process, includes:

- Certain amount of space in memory

- A current working directory

- Sources of input and output such as keyboard, screen, and open files

- A connection with another process over a network

- A program (sequence of instructions)

- Dynamic Part: A program in action

- Instructions that make up a program are actually being carried out

- It is known as a ’thread of execution’ or a ’thread of control’ or a ’thread'

- A thread has access to all of the resources assigned to the task

Processor and Process #

- A processor is the agent which runs a process by executing the instructions contained in its associated program

- There are far fewer processors than processes, so processes get their share of time on the processor

- A process is never offered the processor while it is waiting (for keyboarrd input, for example)

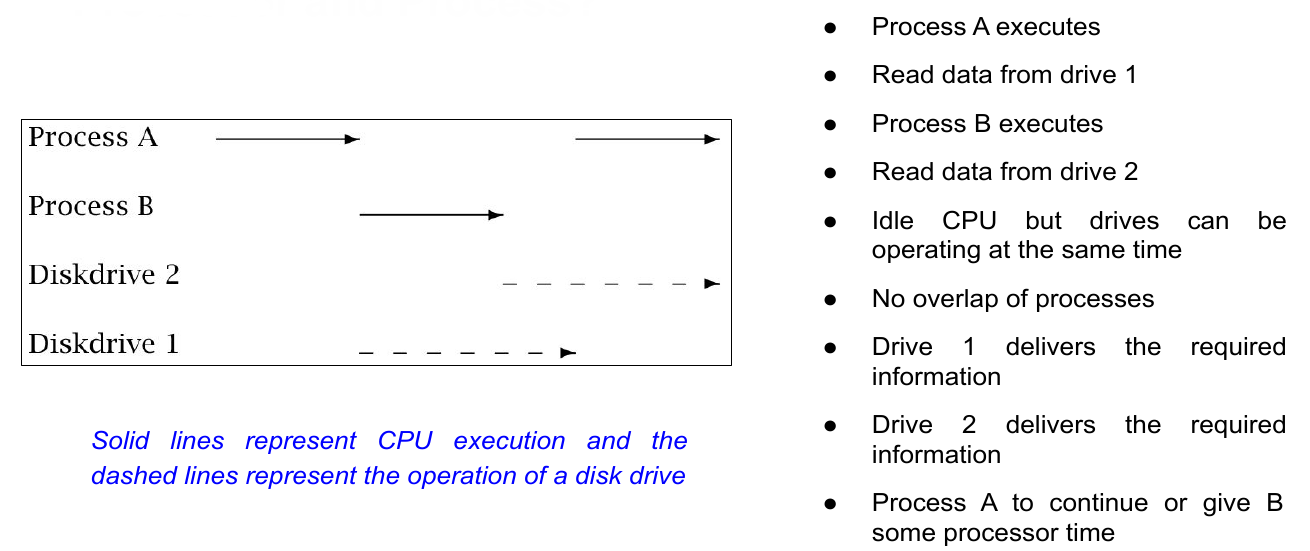

Operating System Overhead #

- It happens frequently that a process begins running on a processor and almost immediately stops again to wait for some input to become available

- The operating system has to save or restore the whole state of the machine as it was at the moment when the process stopped running or begins running again

- Saving and restoring state is overhead and non-productive work, and here it is becoming a large part of the overall work of the computer

- Increasing the size of operations, operating systems become more complex, so requiring even more state to be remembered

Multi-threading #

- The operating systems overhead led to the idea of having a number of paths of execution (threads) through the program at the same time. If one thread is blocked another can execute

- It is not necessary to save and restore the full state of the machine for this, as it is using the same memory, files, and devices - it’s just jumping to another location in the program code

- Each thread must maintain some state information of its own, for example the program counter and general-purpose registers. This is so that when it regains control it may continue from the point it was at before it lost control

- Multithreading enables the processing of multiple threads at one time, rather than multiple processes

- Multithreading is an important utility for many computer programs and increases performance, efficiency, and scalability

Types of Threads #

- User Threads: Above the kernel and without kernel support. These are the threads that application programmers use in their programs. This saves on the overhead of bothering the operating system each time control changes from one thread to another. The operating system gives control of the CPU to a process.

- Kernel Threads: Supported within the kernel of the OS itself. OS handles all the switching between threads. All modern OSes support kernel level threads, allowing the kernel to perform multiple simultaneous tasks and/or to service multiple kernel system calls simultaneously.

Processes, Tasks, and Threads #

- The operating system needs to keep track of processes. It uses data structures called a process control block to represent the different objects it is dealing with

- A process consists of a task, which is the resources allocated, and one or more threads through the code

- It must be possible to represent the one task and a variable number of threads. It needs a static part, and a dynamic part that can grow or shrink

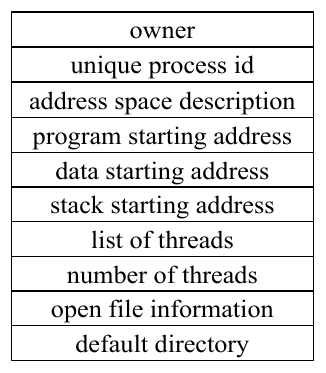

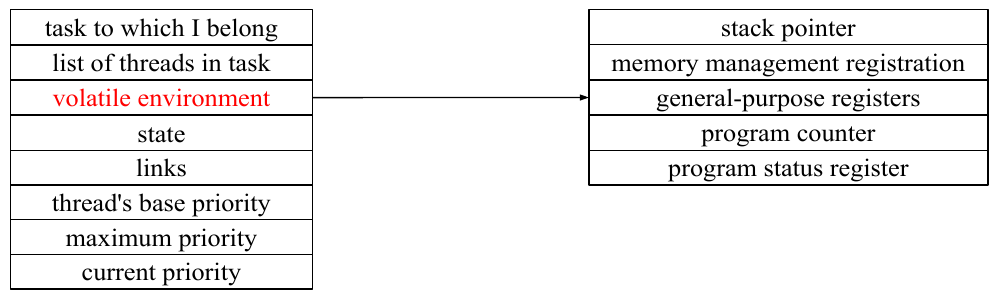

Task Structure #

The structure of the static part, which is the same for all processes.

Thread Structure #

The kernel also maintains a thread data structure for each active thread.

One of the more important fields in this thread structure is the volatile environment, which has fields for the information that has to be saved each time the thread loses control of the CPU.

Thread State #

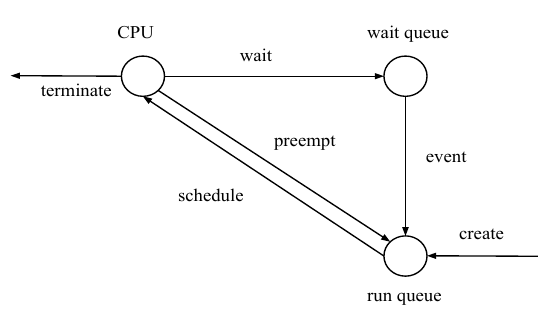

- Each thread has a life cycle of its own, during which it may be in one of the two different states: RUN or WAIT

- The state a thread is in at any particular time is recorded in the state field of the thread structure

- RUN state: Ready and able to do some work. There would be many threads in this state, linked together on a run queue

- WAIT state: For some reason it is unable to use the CPU. A thread in this state is waiting for some event (e.g. physical resource) and threads in this state are linked together in a wait queue

- When a new thread is created, it always begins in the RUN state on the run queue. Eventually it will be given a time slice on the CPU. When this transition takes place is the responsibility of the scheduler

- A thread may stop using the CPU for three reasons:

- Voluntarily: Waiting for a resource - WAIT state

- Termination: Terminating a thread or whole process

- Preemption: OS takes the processor from a thread when a thread has used up its share of time, or when the CPU is needed to handle some more urgent work

- A thread laeves the WAIT state when the event it is waiting for occurs

Context Switching #

- The whole procedure of reallocating a processor from one thread to another

- Context switching is called when:

- A thread loses control of the processor and moves into the WAIT state to wait for a resource to become available

- A timer interrupts to tell it that it has used up its time slice

- It is absolutely essential that the current state of the machine be saved when a thread loses control of the CPU

Thread Scheduling #

- The main objective of the scheduler is to see that the CPU is shared among all contending threads as fairly as possible. The scheduler tries to make the response time as short as possible

- In real-time systems, the scheduler will have to be able to guarantee that response time will never exceed a certain maximum

- Thread priority

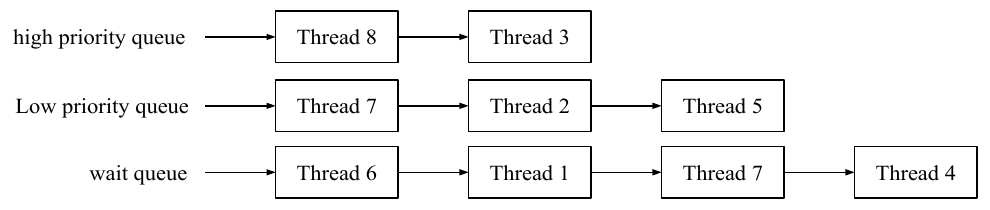

- Thread multilevel priority queues

Thread Priority #

- In an interactive system there is no way to predict in advance how many threads will be running, or how long they will want to run for. They could be scheduled on a first come, first serve basis. But this way some unimportant threads could monopolise the system

- What to do? Order all of the runnable or ready threads by some priority criterion. This priority is allocated to the thread when it is created

- The descriptors of all runnable threads are linked into the run queue, ordered by decreasing priority. The most eligible thread is at the head, then the next, and so on. All the other threads, which are not runnable, are linked together on the wait queue

Thread Multilevel Priority Queues #

Given a system with only two priorities, high and low.

- When a thread is created, it is initially put on the high-priority queue

- If it uses its full time slice this implies that it is compute-bound, so when it is context switched, it is moved to the tail of the low-priority queue

- On the other hand, if the thread gives up the processor to wait for an I/O event, then it can be assumed that it is interactive, then when the event it is waiting for occurs, it is moved from the wait queue to the high-priority queue

- Threads on the high-priority queue are always offered the processor before the low-priority queue, but are expected to keep it for a shorter time